Promiscuous Wireless Packet Sniffer Project

Ray Felch //

Introduction:

After completing and documenting my recent research into keystroke injections (Executing Keyboard Injection Attacks), I was very much interested in learning the in-depth technical aspects of the tools and scripts I used (created by various authors and security research professionals). In particular, I was interested in creating my own software/hardware implementation of these exploits, rather than blindly executing and accepting the work of others.

Obviously, this effort required a deep-dive into the work of some very notable information security researchers such as Travis Goodspeed (GoodFet 2009), Marc Newlin (Bastille Research – MouseJack 2016), Samy Kamkar (KeySweeper 2015), Marcus Mengs / Rogan Dawes (Logitacker 2019), Darren Kitchen (Ducky Scripts – Hak5), phikshun / infamy (JackIt insecurity of Things 2017) and Thorsten Schröder / Max Moser (KeyKeriki 2010).

By taking on the challenge in this manner, my intention was to create an ‘all encompassing’ well-documented account of the many aspects of HID (human interface device) exploitation, allowing others to also benefit from what I discovered along the way.

Research information:

- Nordic Semiconductor

The vast majority of wireless (non-bluetooth) receivers used with keyboards, mice, presentation clickers, etc are based on the legacy Nordic nRF24L Series embedded hardware chips. The ESB (Enhanced Shockburst) protocol used in Nordic transceivers allow for two-way data packet communication, supporting packet buffering, packet acknowledgment, and automatic retransmission of lost packets.

The Nordic radio operates over the 2.4GHz ISM band (2.4 – 2.525GHz) using GFSK modulation, offering baud rates of 250kbps, 1Mbps or 2Mbps and typically transmits at 4dBm (yet capable of 20dBm of power). The nRF24L01+ transceiver uses channel spacing of 1MHz, yielding 125 possible channels.

Nordic transceivers are capable of receiving on 6 pipes (nodes) and transmitting on 1 pipe. They are capable of receiving on all 6 pipes simultaneously, however, can only listen on one channel at a time.

Note: The target’s device address must be known in order to read and write data, to and from the remote device. All configuration and data transmission are handled via SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) using FIFO (first-in, first-out) buffers.

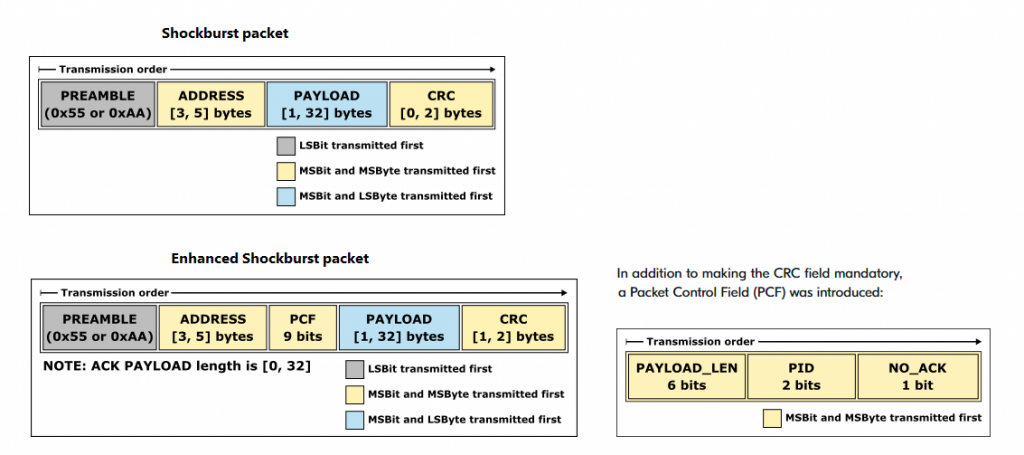

- Nordic’s Shockburst packet protocol

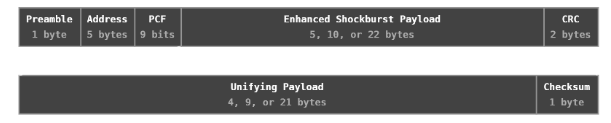

Notice, that the address field is defined to be 3 to 5 bytes (typically 5).

- Promiscuous Sniffing

(http://travisgoodspeed.blogspot.com/2011/02/promiscuity-is-nrf24l01s-duty.html)

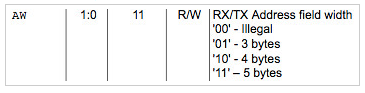

Interestingly, Travis Goodspeed discovered back in 2011 that although the Nordic nRF24L transceiver chipset did not officially support packet sniffing, a pseudo-promiscuous mode existed capable of sniffing a subset of packets being transmitted by various devices. This was accomplished by ignoring Nordic’s specification about the address being limited to 3 – 5 bytes.

Realizing that two bits defined the address size, Travis set the address to the illegal value of zero and got a byte match. By disabling CRC (checksums) he got an influx of false-positive packets that he could then examine for authenticity by manually calculating and confirming checksums. Obviously, without assigning a specific address to listen for, this method would yield an enormous amount of traffic, including false packets due to background noise. Later, Travis created his goodfet.nrf autotune script that significantly improved identifying MAC addresses and beacons. Travis’s research extended the work of Thorsten Schröder and Max Moser of the KeyKeriki v2.0 project (2010).

Note: Although all vendors (Microsoft, Logitech, etc) using the Nordic nRF24L Series radio, followed the same ESB packet protocol specifications, how these vendors defined their specific payloads and hardware interaction varied tremendously. Some used plain text communication with no encryption. Others used encryption on their keyboard traffic but left mice plain text, etc.

Thorsten Schröder and Max Moser (http://www.remote-exploit.org/articles/keykeriki_v2_0__8211_2_4ghz/) built a hardware device based on an NXP LPC17 Arm Cortex-M3 microcontroller with SDR (software-defined radio) firmware. Their device employed two different Nordic radio transceiver modules. In order to successfully transmit, receive, and parse vendors packets they needed to analyze the content and attempt to find and determine any encryption (cryptographic algorithms), sequence counters being used, and find the checksum algorithm (necessary for transmission). Their KeyKeriki project was instrumental in laying the groundwork for other researchers to follow.

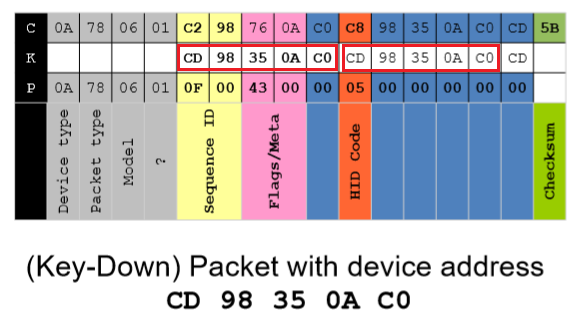

Thorsten Schröder and Max Moser determined the header of the Microsoft Keyboard packet was plain text and the remainder of the payload was encrypted using the device address as the secret key XOR’d with the data.

- Example of Microsoft’s keyboard encryption

In 2016, Marc Newlin (Bastille Research – Mousejack / Burning Man) https://www.bastille.net/research/vulnerabilities/mousejack/technical-details made some significant findings regarding vulnerabilities in quite a few well-known vendor devices (Microsoft, Logitech, HP, Dell, Lenovo, AmazonBasics). See: https://www.bastille.net/research/vulnerabilities/mousejack/affected-devices

Related to his research, Marc Newlin noted:

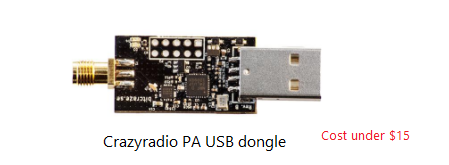

“The Crazyflie is an open-source drone which is controlled with an amplified nRF24L based dongle called the Crazyradio PA.” See: https://www.bitcraze.io/crazyflie-2/

“This is equivalent to an amplified version of the USB dongles commonly used with wireless mice and keyboards. Modifying the Crazyradio PA firmware to include support for pseudo-promiscuous mode made it possible to distill the packet sniffing and injection functionality to a minimal amount of Python code.”

How is keystroke injection possible?

Wireless mice and keyboards communicate using proprietary protocols operating in the 2.4GHz ISM band. Unlike Bluetooth, there is no industry-accepted standard to follow, and vendors are left to implement their own security methodologies. Wireless communication between these devices is accomplished by transmitting radio frequency packets to a receiver dongle attached to a user’s laptop or desktop computer. When the user presses a key (or moves/clicks their mouse), the action is transmitted to the dongle. The dongle listens for radio frequency packets being sent by these paired devices and notifies the computer as the actions occur. The dongle submits this information in the form of USB HID (Human Interface Device) packets.

To prevent eavesdropping, many vendors encrypt their keyboard’s transmitted traffic. The dongle knows the encryption key being used by the keyboard and is able to decrypt the data to determine the action(s) being conveyed. Without knowledge of this key, an attacker would not have access to the plain text data or know the information being typed.

Marc Newlin (Bastille Research) discovered that none of the mice tested used any encryption techniques. This means that the plain text data packets being transmitted by the mouse could be spoofed by an attacker pretending to be a mouse. Marc Newlin also discovered that due to the way some dongles process their received packets, it was actually possible to transmit specially created keystroke packets in place of mouse movements and mouse clicks. In some cases, he found that protocol weaknesses allowed an attacker to generate authentic-looking encrypted packets to the dongle.

In the course of Marc Newlin’s research, it was also determined that there were keyboards and mice that communicated with no encryption whatsoever. This lack of an encryption protocol offers no security, allowing an attacker to inject malicious keystrokes, as well as sniff keystrokes being typed by the user.

Using the Crazyradio PA dongle, it’s possible to sniff the wireless keyboard and mouse traffic being sent to the dongle, which is then converted to USB HID packets on the computer. These HID packets can, in turn, be sniffed by enabling the usbmon kernel module on Linux, thereby displaying the HID code of the key pressed. The captured RF packets can then be analyzed against the HID packets generated to determine vendor-specific protocols.

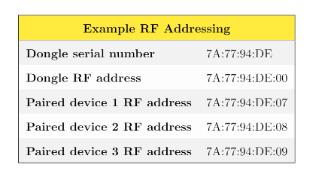

- Logitech Unifying Receivers

Unifying is a proprietary protocol widely used by Logitech wireless mice and keyboards. Logitech’s main focus with the Unifying protocol was the ability to connect up to 6 compatible keyboards and mice to one computer with a single Unifying receiver – and forget the hassle of multiple USB receivers. The majority of Unifying dongles use Nordic nRF24L transceivers, with the remaining devices using Texas Instruments CC254x transceivers. All devices are compatible over-the-air regardless of the underlying hardware.

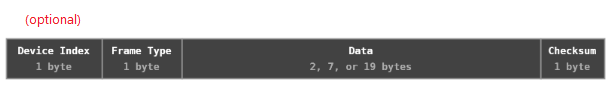

The Bastille Research Team determined that all Unifying packets use either a 5, 10, or 22 byte ESB payload length. In addition to the 2-byte CRC provided by the ESB packet, Unifying packets are also secured with a 1-byte checksum.

Unifying keystroke packets are encrypted using 128-bit AES, using a key generated during the pairing process. The specific key algorithm was unknown to the team, however, they were able to demonstrate encrypted keystroke injection without knowledge of the key.

The dongles always operate in receive mode and all paired devices operate in transmit mode. A dongle can not actively transmit to a paired device, however, it does use ACK payloads to send commands to a device.

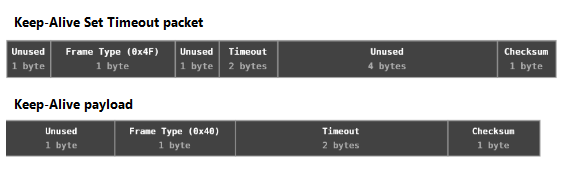

Channel Hopping

When a device is first switched on, it transmits a “wake-up” packet to the address of the dongle that it’s paired with. This causes the dongle to begin listening on the address of the sending device. In order to quickly respond to poor channel conditions, a device sends periodic “keep-alive” packets to the dongle. If a “keep-alive” packet is missed, both the device and the dongle move to a new channel. The periodic timing interval is set by the device. Keeping the timeout interval shorter increases stability (fewer channel changes) but at the cost of high power consumption. To better ensure reliable injections it’s advisable to keep the timeout intervals shorter than the target device typically uses.

Pairing

Host software enables pairing mode over USB. Once enabled, the dongle listens for new pairing devices on a fixed pairing address BB:0A:DC:A5:75 for a period of 30 – 60 seconds. Not all firmware on Unifying dongles can be updated, thus the need to keep the pairing process generic for backward compatibility. When a device is first switched on, it will attempt to reconnect to it’s paired dongle using “wake-up” packets. If it cannot find it’s paired dongle, it will transmit a pairing request to the fixed pairing address to initiate pairing.

Mousejack Device Discovery and Research Tools

Bastille Research provides access to some of the tools they used for their research of exploitable devices. https://github.com/BastilleResearch/mousejack In particular, I found the nRF24_scanner.py and nRF24_sniffer.py python scripts extremely helpful while conducting my own research.

Other Contributors

During my extensive research on this project, I frequently found myself following the work of other researchers and their implementations of keystroke injection techniques. In particular, I want to give a shout-out to phikshun / infamy (JackIt Insecurity of Things). In my previous blog, Executing Keyboard Injection Attacks, I reliably used JackIt to demonstrate my injection attacks to gain root access to vulnerable devices. JackIt also proved to be an invaluable debugging tool while working on my promiscuous scanner/sniffer project. JackIt combines the tools of the Bastille Research Team with the already proven Ducky Scripting language of Darren Kitchen – Hak5, into an awesome keystroke injection attack tool.

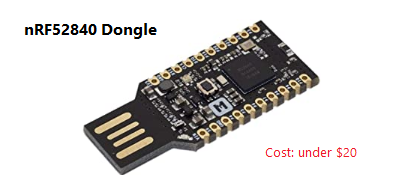

My keystroke injection research project would not be complete without also mentioning the recent work (2019) of Marcus Mengs / Rogan Dawes – Logitacker. Marcus implemented a hardware solution to accomplish discovery, passive and active enumeration, forced pairing, keystroke injection, scripting, and much more, specifically for Logitech devices. Using a Nordic nRF52840 (pca 10059) USB dongle, Marcus flashed his binary code to the dongle, complete with a convenient command-line interface (CLI).

Another major contributor to my keystroke exploitation research efforts is the work of Samy Kamkar author of KeySweeper. Although I didn’t actually attempt to construct his hardware project, I did find the concept to be very interesting from a key-logging exfiltration point of view. Samy’s KeySweeper wirelessly sniffs, decrypts, and logs (as well as reports using GSM) on wireless Microsoft keyboards in the vicinity. His write-up is very informative and quite easy to follow. http://samy.pl/keysweeper/

Building an inexpensive promiscuous sniffer

Parts List:

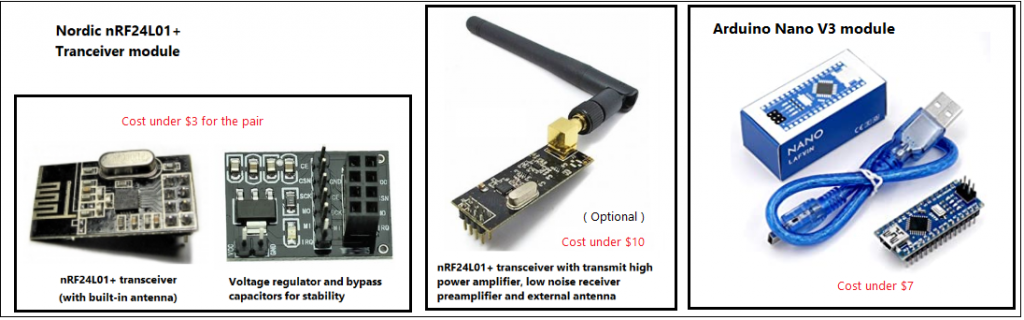

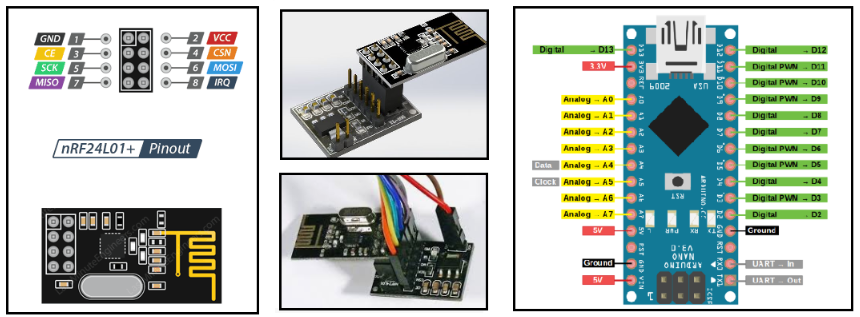

- Arduino Nano

- nRF24L01+ Transceiver module

- Voltage regulator module

- Arduino Nano V3 module

- nRF24L01+ PA LNA long-range module (optional)

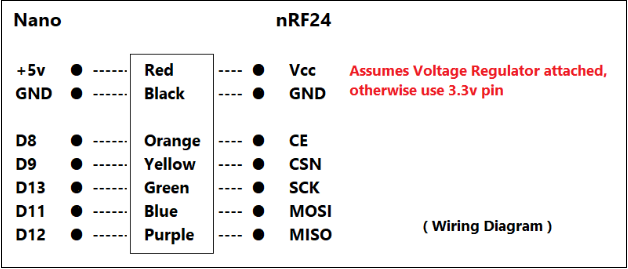

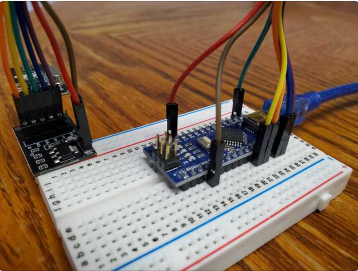

Wiring the hardware is pretty straightforward. The nRF24 radio is controlled via SPI (serial peripheral interface) and the SPI pins are clearly marked on the voltage regulator board. Initially, I breadboarded the project and later fabricated a stand-alone direct-wired version. Either method can be built rather quickly (depending on your soldering and/or breadboard experience). Also, I decided to maintain a color-code scheme throughout my hardware design work. Doing so helps reduce (if not eliminate) the potential for wiring errors.

The Arduino Nano V3 is a breadboard friendly micro-controller board based on the ATmega328. It has 22 input/output pins (14 digital and 8 analog), 32Kb flash memory, 2Kb flash bootloader, and 8Kb of SRAM. The Arduino sniffer sketch will need to be programmed into the Arduino Nano board using the Arduino IDE https://www.arduino.cc/en/Main/Software

IMPORTANT NOTE: You can use the nRF24L01+ transceiver without using the voltage regulator, however, if you choose to do so, you must power the nRF24L01+ with 3.3v maximum or risk destroying the module. If you use the voltage regulator board (highly recommended), you can power it with 5v and the regulator board will safely regulate it down the 3.3v for the radio. Both 3.3v and 5v outputs are available on the Nano board.

Keep in mind, transmitting requires quite a bit of power (PA max setting) and at times the Arduino Nano may have trouble delivering the required power. This can cause intermittent dropped packets, as well as limit the effective range. Using the voltage regulator board significantly improves the overall performance of the radio. The effective range with the voltage regulator board is approximately 100 meters (10 meters without). Using the optional nRF24L01+ PA LNA long-range module with external antenna has been tested and verified to reach 1100 meters (line of sight).

Wiring Diagram

Due to my past success using JackIt for keystroke injections and my desire for a compact device capable of being attached to a mobile phone, I decided to work from Insecurity of Things’ uC_mousejack (phikshun) repository. The uC_mousejack project consisted of getting ‘mousejack’ attacks into a small embedded device, with the form factor of a key chain. The code provides a tool to use Duckyscript to launch automated keystroke injection attacks against Microsoft and Logitech devices. If you have no idea what Duckyscript is, see the Hak5 USB Rubber Ducky Wiki https://github.com/hak5darren/USB-Rubber-Ducky/wiki

Promiscuous Sniffer Code

git clone https://github.com/insecurityofthings/uC_mousejack

- cd /uC_mousejack/src

- mkdir promisc_sniffer

- copy c:\attack.h promisc_sniffer

- copy c:\<path>\promisc_sniffer.ino promisc_sniffer

- cd promisc_sniffer

- (run) promisc_sniffer.ino

Primarily, I was interested in being able to promiscuously scan (passive-enumeration) mac addresses of potentially vulnerable devices in the vicinity and then sniff those addresses (active-enumeration) to determine packet payloads and thereby fingerprint the device as exploitable Microsoft or Logitech devices where applicable.

For this particular project, I was not concerned with the attack mode feature of uC_mousejack and intentionally disabled this function in the code. If you decide that you want to re-enable attack mode, please know that no interaction is required to initiate an attack. Be careful where you use this device. We can not accept any responsibility for how this tool is used.

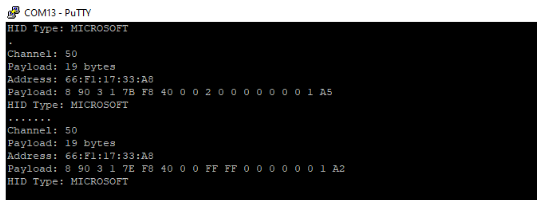

Also note that I modified the code to monitor the keystroke injection being transmitted and display these packets via the serial bus. This data can be viewed using the Serial Monitor (under Tools) in the Arduino IDE or by monitoring the serial port if using platformIO. Alternatively, you can view this data in Windows-based systems with PuTTY.

Sample Output of a Vulnerable Microsoft Mouse 5000 (passive/active enumeration)

(determined by a valid payload length (checksum verified) and fingerprinted HID Type)

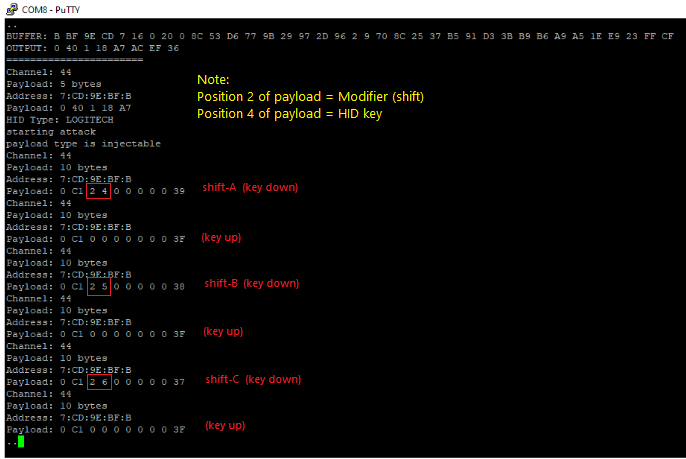

Sample of Keystroke Injection Attack on Vulnerable Logitech K400r Keyboard (injection ‘ABC’)

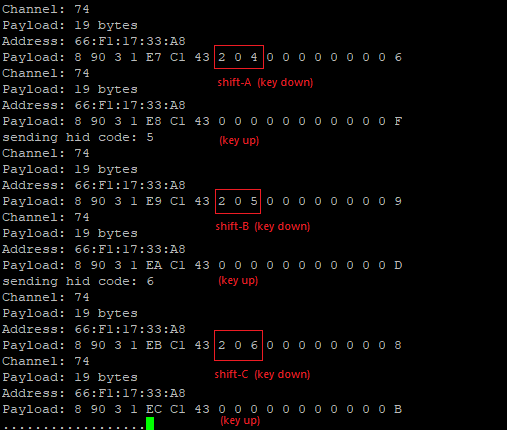

Sample of Keystroke Injection Attack on Vulnerable Microsoft Mouse 5000 (injection ‘ABC’)

Obviously, this is where the fun really begins. Deciphering these proprietary packets needs to be done on a vendor by vendor basis to determine the exact protocols being used by these devices to communicate with the dongle. ‘Stay-Alive’ and ‘wake-up’ packets need to be recognized and fingerprinted, as well as inter-packet timing intervals need to be established and maintained. Marc Newlin – Bastille Research and Thorsten Schröder / Max Moser have done an enormous amount of research in this area and their whitepapers are open-source and publicly available.

Conclusion

As you might have noticed, there have only been a handful of industry-leading security researchers investigating this area of wireless exploitation. And although they have been extremely successful at varying degrees, we can all agree it’s next to impossible to check every keyboard and mouse out there in the wild. Obviously, some of these devices can be updated with new firmware, thereby mitigating the risk (provided they take the initiative to do so), however, there are many devices out there with OTP (one time programmable) firmware, exposing complete systems (and ultimately complete networks) to malicious attacks.

The quickest and most obvious solution would be to swap out wireless keyboards and mice with their wired counterparts in secured areas. Bluetooth devices tend to be a bit more expensive and prone to use considerably more power, however, these too would help reduce the risk of exposure.

From an InfoSec perspective, taking the promiscuous sniffer approach and maintaining a database of known vulnerable devices and their fingerprints could go a long way in helping corporations learn of possible weaknesses in their infrastructure. Ideally, it would be beneficial to be able to go onsite, fire up a portable sniffer, capture addresses and packets, fingerprint these devices as vulnerable or safe, and ultimately print out a log of suspect devices for the customer. Just a thought.

In closing, I will say that I have learned an enormous amount of information about this often overlooked area of wireless exploitation. As more and more security concerns arise in the IoT (internet of things), it is sometimes very easy to overlook keyboards and mice as simplistic and harmless devices. Up until a couple of months ago, I surely did. Going forward, that will change.

References

Goodspeed, Travis. (February 7, 2011). Promiscuity is the nRF24L01+’s Duty. Retrieved from http://travisgoodspeed.blogspot.com/2011/02/promiscuity-is-nrf24l01s-dut

Newlin, Marc. (October 24, 2015). Hacking Wireless Mice with an NES Controller. Presented at ToorCon 17, San Diego, CA

Bitcraze AB. (2016). Crazyflie 2.0. Retrieved from https://www.bitcraze.io/crazyflie-2/

Bitcraze AB. (2016). Crazyradio PA. Retrieved from https://www.bitcraze.io/crazyradio-pa/

Related Work

“KeyKeriki v2.0 – 2.4GHz”, Thorsten Schröder & Max Moser, CanSecWest 2010.

http://www.remote-exploit.org/articles/keykeriki_v2_0__8211_2_4ghz/

https://web.nvd.nist.gov/view/vuln/detail?vulnId=CVE-2010-1184-

“Promiscuity is the nRF24L01+’s Duty”, Travis Goodspeed, 2011.

http://travisgoodspeed.blogspot.com/2011/02/promiscuity-is-nrf24l01s-duty.html-

“KeySweeper”, Samy Kamkar, 2015.

Ready to learn more?

Level up your skills with affordable classes from Antisyphon!

Available live/virtual and on-demand